Tuesday, September 29, 2009

If ever..

Saturday, September 26, 2009

Taken

Liam Neeson stars in this shoot-em-up thriller, as an ex-spy, whose daughter has been, er... 'taken'. The Albanian trafficking gang who have abducted her to sell as a slave to an Arab Sheik, soon learn that they are messing with the wrong man, as he fills them, one-by-one with lead and liberates his daughter. The sub-plot is that Neeson's character was too busy spying to be a good Dad when his daughter was young, but believes he can redeem that time by using his gun-toting skills to be there for her at the decisive moment.

Liam Neeson stars in this shoot-em-up thriller, as an ex-spy, whose daughter has been, er... 'taken'. The Albanian trafficking gang who have abducted her to sell as a slave to an Arab Sheik, soon learn that they are messing with the wrong man, as he fills them, one-by-one with lead and liberates his daughter. The sub-plot is that Neeson's character was too busy spying to be a good Dad when his daughter was young, but believes he can redeem that time by using his gun-toting skills to be there for her at the decisive moment.The plot-line is a reasonable premise for a thriller, and the cast isn't bad either. Somehow though, this film fails to build any emotional intensity, despite the danger, the heroics and the wanton blood-letting. Having recently watched Changeling, a film that grabs the viewer by the throat and refuses to let go, 'Taken' seemed lightweight, trivial, and even un-engaging. Obviously they are totally different types of film, but they do illustrate the rather arbitrary nature of the certification process. The excessive shooting of criminals earns Taken an "18" certificate, even though it's violence is sterile, unaffecting and tedious - certainly not disturbing; whereas the violence seen and implied on Changeling (cert 15) is the stuff of nightmares. Changeling is a true story, with a dark ending, Taken has the standard feel-good ending in which the main characters are OK, and the others discreetly forgotten.

I can't help feeling that doing a movie like this was an odd choice for Liam Neeson - he surely can't be that short of good scripts on offer? Perhaps he harbours a secret unfulfilled ambition to play James Bond, and a lone spy systematically executing criminal masterminds in their secret bases in Taken was as close as he's got! Certainly this effort was below him, with a track recors of having voiced mighty Aslan in Narnia, and played Michael Collins in the excellent Irish historical film of that name.

Taken.. gains only two out of five stars - no more than standard Hollywood fare.

Thursday, September 24, 2009

Book Notes: London Orbital by Iain Sinclair

Many years ago, I heard a book review programme on Radio4 on which they reviewed Edward Platt's Leadville, and Iain Sinclair's London Orbital. I soon found Platt's work and was utterly captivated by it. While the idea of a 'biography of the A40 Road' seemed like a 'minority interest' subject matter in the extreme, in reality this work was a stunningly sensitive portrayal of the human stories which interact with the decisions of city planners, a wonderful collision of poetic prose, urban geography, and biographies. With this in mind, I finally tracked down the other book recommended on that same programme; Iain Sinclair's London Orbital.

Many years ago, I heard a book review programme on Radio4 on which they reviewed Edward Platt's Leadville, and Iain Sinclair's London Orbital. I soon found Platt's work and was utterly captivated by it. While the idea of a 'biography of the A40 Road' seemed like a 'minority interest' subject matter in the extreme, in reality this work was a stunningly sensitive portrayal of the human stories which interact with the decisions of city planners, a wonderful collision of poetic prose, urban geography, and biographies. With this in mind, I finally tracked down the other book recommended on that same programme; Iain Sinclair's London Orbital.The premise of Sinclair's book is promising, intriguing even. The author and various companions set out (in the months running up to the millennium) to walk round the M25, recording their insights into the landscape, history, literature and people that they discover en route. The results turned out to be very surprising.

From the start the author writes in a style which is hard-going. While on some occasions his use of half-formed sentences consisting of lists of adjectives and nouns to describe what he sees, is punchy and effective; overuse of this technique makes it simply affected. Sinclair also enjoys bombarding the reader with streams of half-explained references, a technique which appears to detract from the force of his insights. After all, the informed reader already knows the things to which he refers, while the uninformed remains so, left stranded by Sinclair's constant preference for alluding to things, rather than actually talking about them. Reviews of London Orbital have divided readers very deeply into those who found all this irresistibly brilliant, and those who simply found it impenetrable, and gave up. I found that on every occasion when the density of language, irritating repetition, obscure allusion, and verbose pretension drove me to give-up and add to the little pile of "couldn't finish" books in my study - Sinclair would hit back with a piece of writing so touching, so beautiful, and powerful that I couldn't bear to put it down in case I missed another such moment.

For me the sections of the book which worked were those where I knew the landscape in which he was working. In such sections, the obscure allusions had reference points for me. Of course when I understood his literary tangents, when they occasionally drifted into my frame of reference, the impressions he sought to make were all the stronger. Likewise, when his landscapes were beyond my recollection or his references beyond my reading, the sheer volume of words that Sinclair spews forth became boring - because of his constant unwillingness to initiate the newcomer, rather than simply reward the learned with opportunities for smug self-congratulation.

Quite brilliant were Sinclair's observations on the ring of Victorian mental hospitals which mark out the outer-London ring, which the M25 follows. Built to give "lunatics" fresh air, and to screen London from their reality, they flourished throughout the 20th Century, but are now being developed into soulless luxury apartments. His explorations of these facilities and the way he is able to make the past mix with the present in a intermingled, morbid reality was delicious. His wanderings with companion Renchi, into psychogeography, of ley-lines and the M25 as a vast astrological wheel were dull tangents an already overlong book could have thrived without; trekking through leafy Weybridge in the wake of Diggers however, was magical. The descent into The War of the Worlds between Epsom and Leatherhead is compelling, but the view that the River Thames bridge at Runnymede is some deeply significant and illuminating concrete cathedral is simply putting too much strain even on the psychogeographers desire to write florid prose about the most artless of items. Frustrating too is the lack of a map to see where the writer has got to in any given chapter, given that his ability to wander away from the matter in hand is as great as his remarkable determination to complete the project! Likewise, the frequent references to photographers and cameras, but the total absence of images is strange. Either the publisher refused to add them to the paperback edition (already grotesquely swollen to almost 550 pages) or Sinclair is so convinced of the power of his writing that he has rendered the image superfluous. Not so.

To be fair to Sinclair, there is a tremendous book in here. The trouble is that such a fabulous book would be about 200 pages long, and an extremely judicious editor would need to be employed to cull the wanton excesses from the original. The worst part of the book is actually its beginning, (he doesn't reach the M25 until p125!), and the best parts are all when he stays close to the M25, physically -and in his writing. Where he succeeds is when he stays close to the books initial premise, when he tests the reader's patience is when he departs from this. To be fair, he improves as the book progresses, reducing his words-per-mile count as he goes - possibly realising that unless he did so, a thousand page book was in the offing.

Horrible Histories

Tuesday, September 22, 2009

Monday, September 21, 2009

Last night in Acts...

A summary of the talk is in the diagram below which was my concluding slide. The emphases seem to be that (i) Paul was willing to suffer for the gospel - he went to Jerusalem knowing that persecution awaited him. (ii) He was willing to offend people, but only with the gospel because on all matters of culture, he fitted in with them as much as possible 'becoming like one under the law, in order to win those under the law'. (iii) His 'boldness' is matched with sensitivity to his audience, tailoring his talk to their understanding, and speaking with great respect and politeness.

Sunday, September 20, 2009

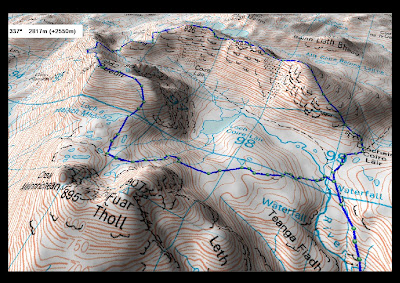

Fabulous 3D mapping

Wednesday, September 16, 2009

Doors Open

This year, the church I'm part of has joined in the event by opening up its premises for the day, combining viewing the now completed premises with an exhibition of local art, from the church, local nurseries, schools and care homes. In keeping with the building the art exhibition is themed around dramatic biblical stories, and this morning I saw one particularly striking Noah's Ark bring carried in from a nearby nursery school. Info below.

Sunday, September 13, 2009

Friday, September 11, 2009

Cairngorms Bonanza!

It is a rare and splendid thing to look up the mountain weather forecast the night before an expedition and read, "No Rain", and "Chance of cloud-free Munro's: 100%"! It's even better when they get it right - and yesterday was just such a day! With the prospect of clear skies, and the whole of the Cairngorms before me, I packed for a long walk - and cycle, setting off soon after sunrise to make the best of the light. From early on it was clear that it was going to be a good day, the golden-orange morning sun shone through the mist still clinging to the surface of the River Isla near Blairgowrie, while glistening off the dewy grass on each bank; a mysteriously wonderful collision of textures and colours.

It is a rare and splendid thing to look up the mountain weather forecast the night before an expedition and read, "No Rain", and "Chance of cloud-free Munro's: 100%"! It's even better when they get it right - and yesterday was just such a day! With the prospect of clear skies, and the whole of the Cairngorms before me, I packed for a long walk - and cycle, setting off soon after sunrise to make the best of the light. From early on it was clear that it was going to be a good day, the golden-orange morning sun shone through the mist still clinging to the surface of the River Isla near Blairgowrie, while glistening off the dewy grass on each bank; a mysteriously wonderful collision of textures and colours.My day-proper started at the Linn of Dee carpark - a place from which many Cairngorm expeditions have begun. I have walked the path from here to Derry Lodge many times, but this time I had a bike with me, speeding my passage toward the high tops. Derry Lodge itself is a forlorn sight, once a hunting lodge in the heart of the Cairngorms, at the centre of a minute community where Gaelic persisted until well after WWII; it is now boarded-up and gently crumbling. I remember feeling similarly forlorn on my first visit to Glen Derry, a borrowed mountain bike broke - and as I fiddled with the broken pedal the party I was with cycled into the distance, leaving me to push the wretched machine all the way back to Linn of Dee. This time, however I was on a brand new bike - its inaugural flight in fact, and it did a great job, speedily eating through the miles. Memories of Derry Lodge are not all bad though; as I dismounted and got ready for walking I remembered camping here with the ever affable Percy Cowpat esq. many years ago. The smell of cigar-smoke and Glenmorangie, the gentle hiss of a heather fire, the brilliant blue-black sky bespeckled by millions of bright stars, framed on every side by the vast-black outlines of great mountains. Such reminiscence was quickly countered with the memory that when we broke camp in the morning to head out towards Beinn Bhreac, the wind suddenly dropped and dark columns of midgies rose from the heather like the fiery exhaust of a steam locomotive, eating our skin and even biting the whites of our eyes!

It was Northwards into Glen Derry that I was bound again on this trip, turning eastwards up the Coire Etchachan, the long climb up onto the Cairngorm plateau, past the little bothy known as the Hutchison Memorial Hut.

Loch Etchachan

Loch Etchachan At the head of Coire Etchachan the scenery changes suddenly and surprisingly. Within seconds, the bleak and bouldery corrie gives way to a pleasant loch, nestling beneath its cliffs -under Ben MacDui's long Eastern flanks. On my visit the delightful scene was made complete by a row of tents nestling on the water's edge, a high level camp-site pitched in pursuit of a Duke of Edinburgh Gold award. From Loch Etchachan, a scratchy path winds its way steeply at first up the side of Beinn Mheadhoin, a great bald whaleback ridge that marks the eastern edge of the central Cairngorm massif. Mheadhoin is noted for its series of absurd granite tors which sit bizarrely along its crown like a row of badly maintained craggy teeth. They do provide some nice scrambling up their sides though - a pleasure not usually associated with the Cairngorms. By the time I stood on the summit tor of Beinn Mheadhoin, a fierce wind was funnelling around the contours of the mountain, so I clambered down and retreated back to the shelter of Etchachan.

My mind's peculiar tendency to anthropomorphise makes me think of Derry Cairngorm as a particularly happy mountain. I am sure that this is due to a combination of its gentle slopes and smooth lines, and the fact that I have so often seen it in sunshine when mountains all around it have loomed as menacing hulks in dark cloud. Climbing it proved to be a bouldery experience, but the views southwards across Deeside and into Perthshire were breathtaking. Climbing onto its summit, I must have moved within range of a mobile phone mast, as my rucksack started to vibrate and a familiar tune rang out. I stopped, unpacked, found the phone, only to be informed that I was in receipt of 100 free extra texts... lovely, but hardly worth stopping for. I must however change that text ring-tone. At the moment, it plays "Lady Day and John Coltrane" by Gil Scott-Heron; a funky little tune indeed. The problem is that the second lines goes, "Ever feel that somehow, somewhere, you lost your way? And if you don't get a help quick, you won't make it through the day!" This may not be what I want to hear next time I am wrestling with a map and compass in fog, rain, zero visibility whilst trying to navigate some precipitous ridge! In the meantime if you see someone in the Scottish hills screaming "SHUT-UP" at his rucksack, it just means I have received a text!

There are some guidebooks which talk about 'conquering mountains', to describe ascending them. I think that such talk is foolhardy. To wander up a mountain in summer conditions is not to conquer it, merely to walk with it, to spend time with it. In contrast, I find that to stand in these great mountains and to tremble before their grandeur is more akin to being conquered by them; surrounded and overwhemed by them, to hold them in awe. Of mountains, so of God; perhaps illuminating what a Psalmist once wrote: Your righteousness is like the mighty mountains, your justice like the great deep. O LORD. For such granduer can be contemplated, engaged with, even perhaps wrestled with - but never conquered. Such thoughts filled my mind, and seemed to press home with an unusual urgency as I strained hard up a long climb, with a summit ahead of me, and the ground falling away on either side, Glen Derry on one side, Glen Lui on the other.

From Derry Cairngorm, I made my way back onto the central high ground of the Caringorm plateau, working my way back Northwards until I hit the busy trade route, linking Cairngorm and Ben MacDui. The Duke of Ed party had broken camp and were making their way up the long climb ahead of me, labouring under packs heavier than mine. I might have envied their night in the wild, but I didn't envy the loads they bore. It's seventeen years since I last walked this track, and there were a few things I remembered, the most distinctive of which was gash in the rock, next to the path - a spectacular gully eating into the mountain; a talking point in summer and a death trap when corniced in winter conditions. I remember posing for photos here all those years ago with Big Darren, The Rake and Crazy Jim.... and wondering what became of them all.

If Derry Cairngorm seems like a 'happy' mountain, then Ben MacDui is quite the opposite; large, dark, brutish, mysterious and foreboding. I trudged alone up the path towards its trig point, perched high on a cairn, the second highest point in Scotland - and could quite understand why fevered imaginations have run from the presence of the Big Grey Man of Ben MacDui. The Big Grey Man was not in attendance as I strode over the Ben's rock-strewn summit, yet the melancholy dread of the place was dense as I passed the ruin just short of the top; where the only sound was the howling of an anguished dog, which I heard but never saw. Two things have changed since I last stood on Ben MacDui, this time there was no dead-man lying in the boulders awaiting collection by the mountain rescue services; no helicopter hovering low, engines throbbing, swooping to collect the departed remains. The other difference was that the summit has been absolutely covered in cairns, shelters, seats and all sorts of bouldery creations. To be honest, I don't mind the odd cairn here or there - on a summit, or to mark a junction of paths; but this was grotesque, as if Fred and Barney had hosted a world championship of Jurassic Jenga, but all the contestants had abandoned the game in mid-session. Perhaps like Professor Norman Collie, they hurriedly fled the place in fear of the Big Grey Man!

The descent from Ben MacDui alongside the Allt Clach nan Taillear is awkward, and in mist would require some very canny navigation. It leads to a high col and over a swooping ridge to the ascent of Carn a Mhaim. The hill looks very easy when viewed from the likes of Braeriach, but at the end of a long day, with a brooding headache - it was a long pull. The sun, dipping low, and casting long shadows and orange patterns over the hills made a stunning backdrop to the views over the Lairig Ghru and down into Glen Lui far below. A decent path, drops from this hill, down to the Luibeg Bridge (which I actually found this time!), and then on back to Derry Lodge. After a long, hard strenuous walk, I was delighted to see the bike, leaning against the side of the Glen Derry mountain rescue station. Bringing the bike was a great idea, I have trudged the long miles back to Linn of Dee often enough to be grateful to spin swiftly along it and back to the car, to a rest, a drink and the drive home. Days as good as these are a treat to be savoured, an opportunity to be grasped, and an experience for which to be profoundly thankful.

Tuesday, September 08, 2009

Getting Geeky with the Archive

One of the secrets which the dismantling of our old attic space revealed was an on old video camera, complete with leads, tapes and some amusing footage of our three kids when they were small. The kids really enjoyed looking at themselves as babies/toddlers on the tiny screen of the camera, which inspired me to see if the films could be imported to the PC for a little editing and then watching on a decent screen. As readers of this blog know, I also discovered that my PC had Windows Movie Maker, my first experiments with which are found here.

The old Sony Handycam camera however didn't seem to like my PC - despite all the relevant USB cables being shoved in the right holes. Some online searching revealed that the older Sony cameras are incompatible with Vista va USB, that Sony blame Micosoft, and vice versa. The same forums did suggest that connecting via Firewire would sort the problem out though. The result of this is that for the price of a foot or two of firewire - I can now import the hours of film that have been collecting dust in the attic for the last five or so years. On the films there are plenty of dreadful sections when the camera was switched on by mistake. When I saw these I hoped that they might contain scandalous admissions or accusations made by family members unaware that the tape was running; sadly all it revealed were reams of footage of feet crunching across gravel. Still - as these are on the PC, editing these out to leave watchable extracts is a simple, if somewhat time consuming process.

Next I discovered that a lot of the shorter film clips which I have on my PC were shot from an ordinary digital camera. These too can be slotted into the edited films at the relevant places.... mostly. The cameras we have owned over the years have mostly shot their movie clips as AVI's, which indeed slot straight into Windows Movie Maker. One camera however, captured its movies in Quicktime, which Movie Maker doesn't accept. Back online I discovered RAD Video Tools, a piece of freeware that had lots of recommendations as a tool for changing formats. Having downloaded that, and successfully making all my .mov files into .AVI's I can now work my way through chopping editing and putting together the film clips from the different years for the children's lives.

RAD Video Tools had a nice surprise in store for me too. When I opened up the "output" choices in the menu, alongside the various movie formats, it also had options for jpeg, gif and bitmap! In other words, it can separate out each individual frame as a picture, in massively higher quality than freezing the frame on a media player and capturing the screen. The photo of Loch Ossian on Rannoch Moor (above) was captured this way. One thing to note though is that even edited down to three seconds, there were hundreds of frames captured, so don't try that with a long clip!

The next problem is what to do with an old High-8 video that we have also found in the attic, which we used almost ten years ago. It has no USB or Firewire connections, and only outputs a signal on two jacks, audio and video. I am told that a gadget to convert the signal will cost me £90 - surely there is a cheaper solution than that?